The first moments of enfolding drop us into a park while eerie, metallic scratches and sharply bowed tones grow underneath. It’s an unexpected soundscape for a string orchestra. When I think of a string orchestra, I often conjure the sounds of 19th century romanticism—lush, warm sound driven by soaring cellos and sweet violins. But string instruments are capable of more than just those associations: their wooden bodies can be percussive, their strings can vibrate with gusto or hum in quietude.

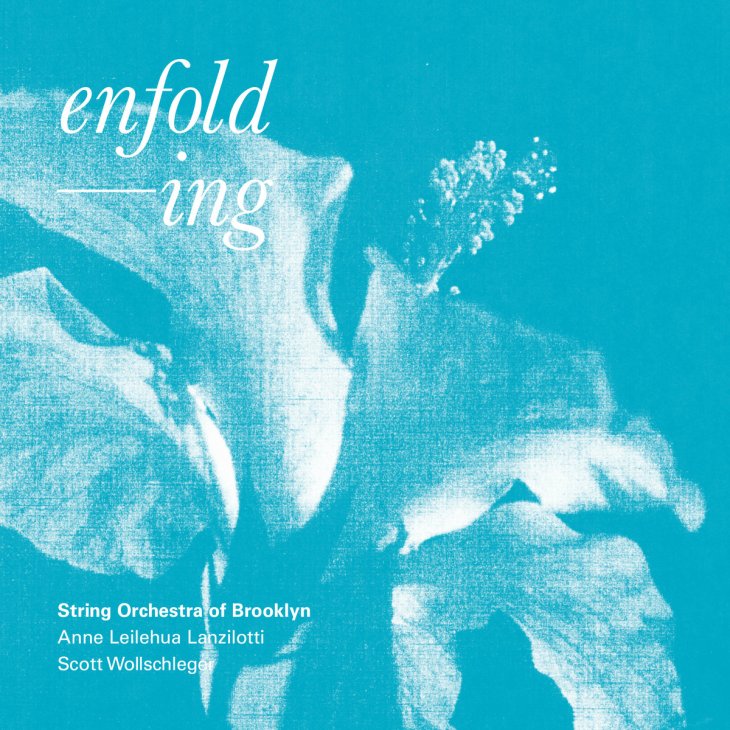

On enfolding, composers Anne Leilehua Lanzilotti and Scott Wollschleger explore the extended possibilities of the string orchestra, finding new ways of expressivity within an age-old form. Recorded in 2020 and 2021 by the String Orchestra of Brooklyn, enfolding opens with Wollschleger’s quarantine-composed work Outside Only Sound and follows with Lanzilotti’s nine-movement epic with eyes the color of time, which was a finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Music. Each piece employs sounds like scratch tones, forming music driven by complex textures more than interwoven melodies. In the end, both works illuminate the lesser-heard side of the string orchestra, the sounds that hide just beneath the surface.

Outside Only Sound was first written while lockdown restrictions were in place; the assignment was to write a piece that could be rehearsed quickly and performed outside. There’s a sense of spontaneity to the music, driven by random triangle and bell taps and sporadic string bowings, all layered over the ebb and flow of the sounds of people enjoying a nice day outside. These sounds don’t mesh together: Instead, they’re content to clash, hanging in a feeling of dissonance and stillness that seems reminiscent of the time in which the piece was written. This is music that uses texture to conjure feeling, letting abstract sounds tell their own stories.

Lanzilotti’s with eyes the color of time similarly uses extended techniques to paint pictures, this time writing music that’s inspired by works on display at The Contemporary Museum in Honolulu. The piece collages together a variety of different sounds and styles: Movements like “the bronze doors” feature distant, wispy scrapes, while movements like “enfolding” are built on lush, rolled chords reminiscent of J.S. Bach. In bringing these disparate styles together, Lanzilotti is able to form sounds that feel nearly tangible.

The fourth movement, “les sortilèges (the wound / the torn page),” feels like the climactic point of the piece, and it expertly uses this blend of contrasts. The movement opens with a full-bodied, deep, and descending string melody reminiscent of pieces like Dimitri Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8 or the famous cello solo from Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. Here, that lamentation expands outward, filled out by clocklike, low pulses. Gradually, hollow scratches begin to enter and take over, turning the chorus of forlorn string melodies into a chorus of frog croaks and swarming gristles. But the transition from one soundscape to the other comes easily, as simple as the motion of a bow against the strings. Those dramatic shifts drive with eyes the color of time as a whole, creating its visceral sensations.

In the last breaths of with eyes the color of time, sound is but a haunted wisp, fading away yet ready to transform into whatever comes next. There’s an immense history of orchestral music that seems to continuously loom over composition, but there’s always ample room for trying something different. enfolding offers one path, showcasing the many capabilities of string instruments beyond the usual way of playing them. Perhaps most importantly, through their music, Lanzilotti and Wollschleger remind us that the string orchestra can become anything you can dream it to be.